SPECIAL REPORT: Haiti

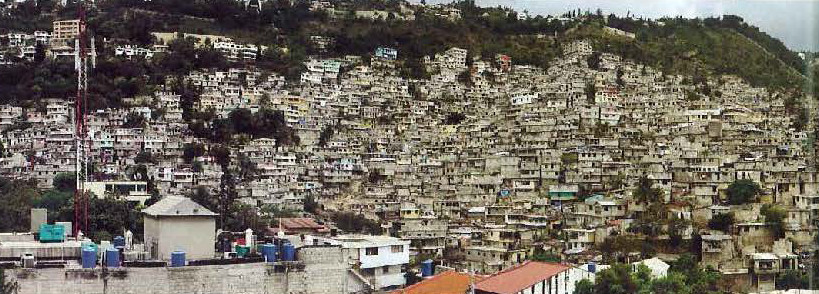

In 7.0-magnitude earthquake that struck Haiti on January 12 was one of most deadliest natural disasters in past century. More then 230,000 people were killed, and a vast number of buildings were destroyed or left structurally unsound. Today 1.5 million residents remain homeless.

In mid April, I headed to Haiti with Tom Sawyer, a senior editor at our sister publication Engineering News-Record to report on the destruction and to witness firsthand the early stages of rebuilding effort. During our weeklong trip we met with local and foreign architects and visited more then a dozen sites in Port-au-Prince and outlaying areas. Here, we present a series of snapshots from our expedition, with expanded coverage online.

Ruble removal is a huge problem in Port-au-Prince. According to some reports, collapsed buildings generated up to 78 cubic yards of debris, much of it still clogging the streets (right). We often saw man digging through the wreckage, looking for salvageable rebar and concrete. Indeed, Haitians do what they can to get by. It’s not uncommon to see merchants selling produce alongside steamy mounds of garbage (right).

A good night sleep it’s hard to come by. On April 20, we traveled to the Bon Repos, or “good rest”, a district in northern half of Port-au-Prince. A rainstorm the prior evening had hit the area hard. The unpaved roads were flooded, as was the Centre D’hebergement de Crajadel camp (left), where flimsy tents made of sticks and bedsheets set in large pool of stagnant, brown water. The camp’s leader Lucien Simeon, says 400 families, or more than 1,000 people, were forced to relocate. Asked where they went, he gestured with his arms that they had simply disappeared dispersed.

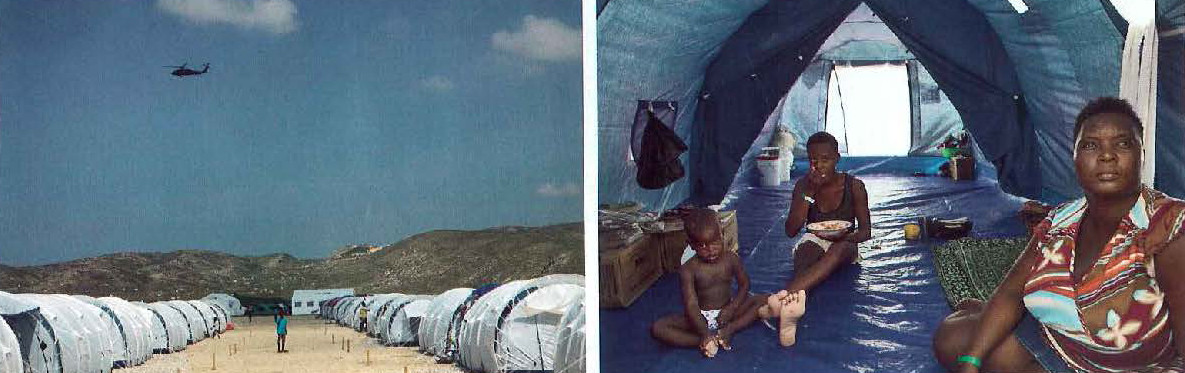

Some eventually end up at Corail-Cesselesse, a new camp on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince (above left and right). Thousands of refugees are being moved to this desolate site, where white tents sprawl across an inexpensive swath of gravel-covered land. People bring whatever meager belongings they still possess and rely on donated food.

On April 21, we visited the camp of Architecture for Humanity’s (AFH) Haiti team. “We came on a fact-finding mission, to see if we can be of some help,” said Eric Cesal, AFH’s regional program manager. He noted that Corail-Cesselesse is intended to house 35,000 residents.

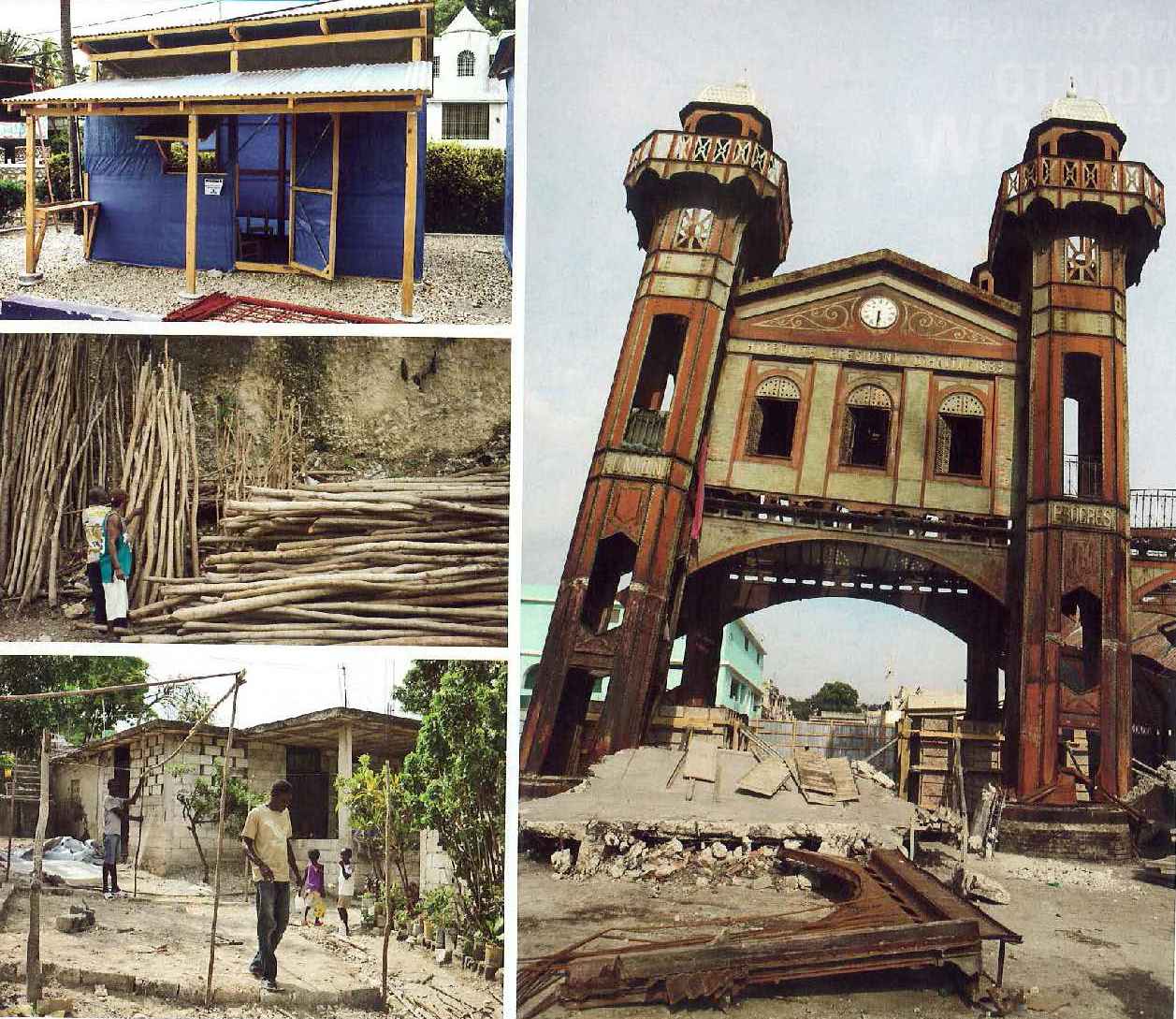

Transitional shelters are beginning to supplant emergency tents. In the towns of Cabaret and Léogâne, Habitat for Humanity plans to erect 1,000 temporary, upgradable dwellings. The structures – largely designed by volunteer Robert Busser, AIA, a Philadelphia architect who traveled to Haiti in April – have either wood or steel framing and anchored to the ground with concrete-filled buckets. Eventually, the tarp cladding can be replaced with a sturdier material, such as plywood or bricks.

Many Haitians aren’t waiting for foreign aid. One morning while driving to Port-au-Prince, we met Cesar Ernst, 35, who was constructing a shelter (bootom left) near his destroyed home. His resources: cinder blocks, shreds of fabric, a tattered tarp, I wooden poles – a common building material in the city (center left). Once this make-shift residence is complete, it will accommodate 15 people.

While housing is a primary concern in quake -ravaged areas, there are other types of projects under way. John McAsian, a prominent U.K. architect who has worked in Haiti for several years, has been hired by Digicel, a mobile phone company, to restore shattered Iron Market (right). Erected in 1889, this once-bustling landmark sits on the heart of the downtown Port-au-Prince . The goal is to get it up and running by the end of 2010.

Architecture for Humanity was launched in 1999 in today has 63 chapters around the globe. in 2009, the nonprofit organization began working in Hairi; this past March, it opened a field office in Pétionville, a district in Port- au-Prince.

The office has three people on staff (above, from left): Schendy Kernizan, a designer fellow from Philadelphia who was born in Haiti; Eric Cesal, a Washington, D.C., designer who holds master’s degree in architecture, construction management and business administration; Yves François, a New York architect who returned to his native Haiti last year and now runs his own firm there, ECOFRA.

AFH focuses on long-term projects rather than emergency services. In Haiti, the organization aims to design and construct community values, with emphasis on schools. The January earthquake reportedly wiped out 4,000 educational facilities.

in April, the AFH team spent much of its time on site visits, hunting for ideal locations to build. “It is a central part of the process,” says Cesal. “There is no substitute for having boots on the ground.”

Interview with Yves François, Haitian Designer

After decades of practicing architecture in New York, François returned to his native Haiti to set up a design and construction firm in Port-au-Prince. Here, he speaks candidly about his experience working in the troubled island country.

Q&A With Haitian-American Architect-Engineer Yves François

Yves François is a firm owner who defies convention. The 45-year-old designer was born in Haiti but spent most of his childhood in Brooklyn. In 1986, he earned an architecture degree from the New York Institute of Technology and went on to work for 10 years at Pepsico as a facility manager and architectural consultant. He later held similar positions at Philip Morris and Cablevision.

In 2004, after nearly two decades working in corporate America, François started re-evaluating his life. “You finally reach a threshold. There’s got to be more to life than making a six-figure salary,” he says. In addition to founding a Brooklyn-based development company that specializes in rehabilitating old properties, François began focusing his energy on Haiti.

In 2006, he started donating money to a school in Jacmel, a coastal town, and took steps to establish an architecture and construction firm in Port-au-Prince. In early 2009, he made the bold decision to fully relocate to Haiti, to see if he could “make a difference” in creating a safer built environment. The move surprised his family. “They thought I was crazy,” he says. “I still believe it was the right thing to do.”

Post-earthquake, François continues to operate his firm, dubbed ECOFRA (derived from his children’s names, Erin and Chandler). He also is working as a consultant for Architecture for Humanity, which opened a Haiti office in March. We recently spoke to François about practicing architecture in Haiti, dealing with corruption and how he is playing a role in the reconstruction effort. François spoke with McGraw-Hill Construction Deputy News Director Jenna McKnight.

How many people work for ECOFRA?

I have a professional staff of 10 to 12. Because of the construction projects we do, I sometimes employ upward of 100 people. What is the role of the “architect” in Haiti? I’ve never been called an architect. They call me an engineer. The word “architect” is not in their vocabulary. I’m trying to educate people.

What does it take to set up a firm in Haiti?

When I first came down, I didn’t know anything from a business point of view. I made a lot of mistakes and lost a lot of money. Then I realized it’s not that complicated. You go to the government tax office, file a business certificate and get your tax ID number, which is like an EIN [U.S. Employer Identification Number]. It takes about six months.

Do you pay taxes?

Yes, but the majority [of people] don’t. People ask why I pay taxes, but I’m an American. Can foreigners set up a company in Haiti? Yes, absolutely. There are tons of them here. NGOs [non-governmental organizations] have to register, too, but many operate without it, as they don’t have the infrastructure to get everybody registered.

How do you get commissions?

Word of mouth. With a U.S. education, it’s a lot easier.

Do you work on government projects?

Very few. Most of my work now is through international organizations and friends who are well off. Government work is possible, but so far I’ve stayed away. It’s something I’m going to look into, especially because most of the work is being funded by international organizations. Hopefully, it will be a level playing field. RFPs are advertised in the newspaper [and] knowing someone on the inside helps.

I hear there’s a lot of corruption in Haiti. Is that something you encounter?

Every day. I keep telling them, “No, no, I don’t operate like that.” For example, I import construction materials and equipment. One of my shipments sat at the port for six months. The government official saw my big equipment, and he said he just bought a piece of land and needed to use the machine. Being [myself], I told him, “You can keep it. When you’re ready to give it to me, let me know.” I eventually got the call to come pick up my equipment. If you want to go that route, it can take months. Or you can pay the bribes and keep moving. People who have government contracts often want 25%.

Were you worried you wouldn’t get back your equipment?

Oh yeah, I was worried. It was a couple hundred thousands dollars’ worth of stuff. But if you believe in something and want to make a change, you have to hold your ground.

In addition to corruption, what are some of the others challenges of working in Haiti?

Safety is an issue. Workers will show up at a job site wearing sandals. I try to talk to them about safety, why they need to wear a helmet and boots. It costs money to get that stuff, though. Sometimes, I’m able to give them the basics, like T-shirts and shoes.

Are Haitian workers skilled?

Not really. Here in the office, for instance, I’m doing a little sheetrock work. I literally had to show them how to hold a screw gun and explain why we have to install studs. Sheetrock is a novelty here. Most construction is concrete block and poured concrete. They’re excellent at that stuff, but I’m trying to show them best practices. It’s rare that I see a plumb wall in Haiti. There’s a lack of tools and a lack of eye to know that a wall is not straight. It’s a whole education process, and with my background in running construction projects, I’m able to do that.

How many projects do you have on the boards right now?

We recently completed eight projects. We’re hoping to sign contracts within the next six months. We’re looking for a few architecture projects, a couple homes. And we’re renovating the office building where I work. In Haiti, design fees are so low, you have to be able to do both design and construction. Most of the firms here are design-build—I would say 90%, based on [my] exposure to local architects.

How many architects are there in Haiti?

We hosted a meeting with Architecture for Humanity and Habitat for Humanity, and there were about 35 people there—some students, some professionals. My guess is there are 50 to 60 practicing architects in Haiti, and 25% were educated abroad.

Are there architecture schools?

There are a few schools. All of them collapsed [in the earthquake] and are operating out of a tent. I have a couple of students working with me now. To my surprise, they are very, very good. I thought the education system here was archaic, but they really know their stuff. They are very computer literate; they know AutoCad, SketchUp. They need to learn 3D Studio and Rhino, [to] which I’m introducing them with the help of Architecture for Humanity.

How much does it cost to attend architecture school in Haiti?

It’s around $1,000 to $2,000 per semester. Most students come from families that can afford it. It’s a five-year B.Arch program.

Are there graduate-level programs?

No, most of them go abroad for additional education. They go abroad and don’t come back. I’m pretty unusual—and crazy. Go in front of the U.S. Embassy [in Port-au-Prince] and see how long the lines are. That’s the dream: to pack up and go.

Are Haitians ready and willing to rebuild?

Absolutely. The sad part is, I’m starting to see signs that a lot of the work is going to non-Haitians. The Dominican Republic is getting a lot of contracts now. When I submit a proposal now, I’m competing with Dominican firms working in Haiti. I hope it’s a temporary thing.

But you’re an American…

But most of my employees are local people. They don’t have good skill sets, so it costs me a little more, but the… …wages are lower. After a year or so, I’m starting to see a difference, especially in their work ethic. I hope foreign firms come and have the same mind-set. We ought to take the time to train Haitians. The foreign companies will make a boatload of money and leave in a year or two, and the Haitian guys still are going to be untrained. I’m focusing on getting local people trained on best practices, so they can rebuild Haiti over the next 10, 20, 30 years.

Does Haiti need foreign architects?

I believe so. Haiti is going to rebuild. We have 30 to 50 architects locally. I don’t think that’s sufficient. Then again, I don’t think it should be some architecture firm in New York that stays in New York, designs a building and ships a set of drawings down to Haiti. Most firms in the U.S. are afraid to come to Haiti, post-earthquake. I see some construction firms walking around with big security guards—two or three bodyguards. If you think it’s that bad, don’t come.

Do you think construction companies will want to work in Haiti?

I think so. Look at Turner—they’re around the world, including parts of the Caribbean. Why not Haiti? There are money-making opportunities here, especially on the development side. The country needs to be developed. That’s why I’m here.

Do Haitians welcome foreign workers?

Absolutely not. You’re competition. They’ve been struggling for most of their lives. They see American companies coming through, and they want to share the pie with them. In America, there is the whole notion of [minority-owned] business enterprise, where, say, 25% of your business has to go to minority-owned businesses. I think the same thing needs to happen here in Haiti—25 percent has to go to locals. You have to be able to train people and show results.

What will it take to rebuild Haiti?

It’s going to take some strong code of ethics and some good, smart people from outside of Haiti to join hands, literally, in helping develop and bring good architecture to this country.

05/26/2010 By Jenna McKnight ARCHITECTURAL RECORD

Photo: Aric Mei. François, born in Haiti but raised in Brooklyn, derived his firm’s name from the names of his children, Erin and Chandler.